Galerie Michael Werner is delighted to present the exhibition RÉQUICHOT. A catalogue accompanying the exhibition will be published with texts by Philippe Dagen, Stefan Ripplinger, Gérald Moralès and Roland Barthes.

The exhibition will be on view from January 31 until April 11, 2026.

Press release

To this day, there is no way to clearly categorize the work of French artist and writer Bernard Réquichot (1929–1961). His output is less a matter of a rounded oeuvre and more of a trace, an exploratory attempt to grant the image a space beyond the realm of the visible. Despite, or precisely because he was only creative for such a short period of time, and it ended abruptly when he fell from the window of his studio in Paris, Réquichot bequeathed us a radical enquiry into painting, and the depth and many sides to his work remain unsettling to this day.

In the years while he was training, he created images such as Vanité (1952) that were inspired by religion and took part in restoring Romanesque frescos (something that left an emphatic mark on his own work); in the 1950s, he took on board Cubist techniques and produced his first abstract paintings, such as Le tombeau de William Blake (1954). This image, on the one hand, references William Blake’s The Grave, a cycle of illustrations Blake made to visualize Robert Blair’s poem of the same name. On the other, it highlights an understanding of death that construes it not as the end but as a transition: as liberation and entry into a deeper, less limited reality. To this extent, it is hardly surprising that in a letter dated January 11, 1954, Réquichot expressly refers to Blake’s images and poetry.

Réquichot is one of those rare species of artists who condition their visual language by devising a genuine pictorial semantics. It is one that has nothing to do with the surface of the painting or some mental space but is connected with in increasingly ritualized form the drive to tease out the limits of painting and find a way of capturing the indescribable. The flight into the pictorial space entails freefall from the lifeworld and at the same time immersion in precisely that pictorial space. Réquichot enters into a profound conversation with himself and does so in order to expand the inner space of what painting can achieve, taking his cue from his own processes of animation – in which death is not a rupture but a change in forms, rhythms, and consciousness. These arise in Réquichot’s pictorial worlds by dint of inner acts and not through some ambiguous approach to religion.

His images and texts are exaggerations that are steeped in time; whenever he found himself erring or doubting, he insisted, fully aware of Blaise Pascal’s adage, that no one dies so poor as to not leave something behind. For Walter Benjamin, there is no real story to tell without death, only information to be passed on. Benjamin’s essay, published in 1936, on The Storyteller becomes the yardstick for the loss of meaning in Modernism. Where Benjamin construes death as the origin of narrativity, Réquichot puts his finger on the point where and when narration falls apart and all that remain are traces. Few painters have pursued this painterly trace in a more uncompromising vein, once the self-evident seems out of place and the incomprehensible seems obvious.

This is the starting point of Réquichot’s oeuvre.

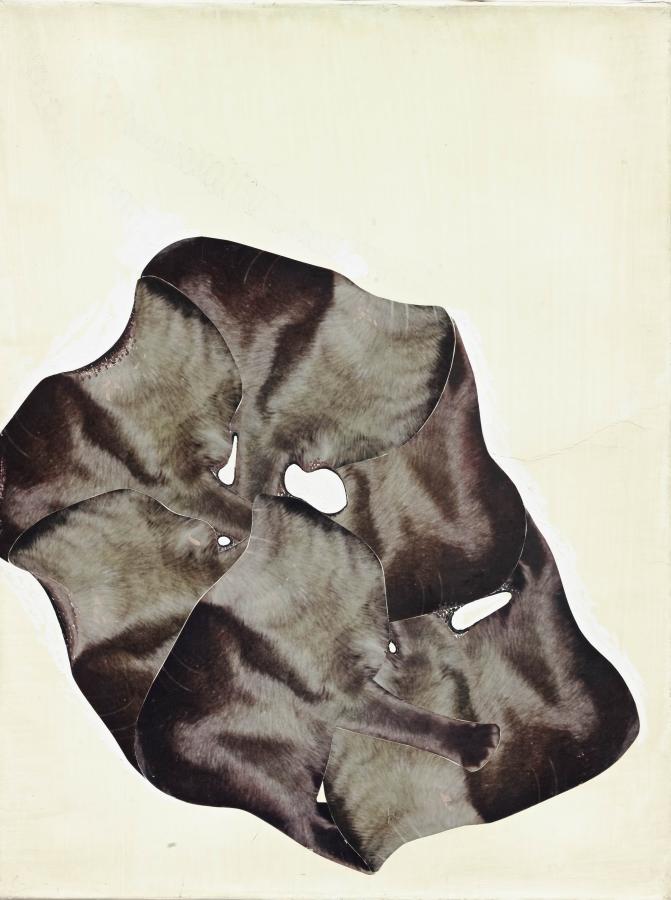

In his collages dating from 1957 to 1960 Réquichot explores a kind of anti-physical quality, starting from the assumption that human thoughts about culture, art, and society originate in personal solitariness. His artistic observation achieves something close to that mystic depth which Claude Lévi-Strauss termed the theory of “wild thought”. The objects in the images lose their names: Shading and brightness form independent systems, pose questions that have no need for roots in science, and cannot be attributed to a practice either; rather, they derive their existence and value exclusively from the chords that are struck between the soul, the eye, and the hand in Réquichot’s art.

He must have been aware that death sanctions everything an artist can report on. Réquichot borrowed his artistic authority from death. In other words, his images, and in a very special way his Reliquaire such as Nokto Keda Taktafoni (1959–1960), refer back to natural history. By resorting to the ephemeral means of expression used by ostensibly primitive cultures, such as bones, he rejects any perfect formulation and highlights a personal cultic site which officially went by the name of “Individual Mythologies” for the first time at documenta 5 (1972).

In this regard, we can grasp Réquichot as both a herald and an outsider: as an artist who only three years after his death covertly developed a different hierarchy of painting at documenta 3 (1964). His pictorial worlds confront us to this day with something indescribable with all its vibrant impact: with something that cannot be pinned down, because it cannot be assigned neither to life nor solely to death. Such an artistic tale of life as that told by Réquichot erases the line that customarily divides the two.

The exhibition RÉQUICHOT will be on view from January 31 through April 11, 2026. The show is accompanied by a catalogue with texts by Philippe Dagen, Stefan Ripplinger, Gérald Moralès and Roland Barthes.

Opening hours are Tuesday to Friday, 11 am - 6 pm, and Saturday, 10 am - 4 pm.

For any further inquiries, please contact the gallery at galeriewerner@michaelwerner.de or visit our website: www.michaelwerner.de.

Follow the gallery on Instagram.